RECENT POSTS

- Introducing modelx-cython: Boosting modelx with Cython Compilation

- A First Look at Python in Excel

- Enhanced Speed for Exported lifelib Models

- New Feature: Export Models as Self-contained Python Packages

- Why you should use modelx

- New MxDataView in spyder-modelx v0.13.0

- Building an object-oriented model with modelx

- Why dynamic ALM models are slow

- Running a heavy model while saving memory

- Running modelx in parallel using ipyparallel

- All posts ...

Why Excel is better than Python

Mar 6, 2022

Last update: August 5, 2023

Actuaries, quants, and other mathematical finance experts frequently use Excel. Despite knowing it’s not the best practice to use Excel for complex modeling, they persist in doing so.

Excel has its drawbacks. It is error-prone due to manual data entry into small cells on large sheets. Formulas with nested parentheses and cell references by addresses complicate understanding. Workbooks are difficult to compare, and they don’t integrate well with version control systems.

Despite these issues, actuaries cling to Excel. Some attempt to introduce Python, or their preferred programming language, with the aim of replacing Excel. However, in most cases, these initiatives fail, often because users are deeply committed to Excel. Without substantial exploration, they may prematurely conclude that Python is unsuitable for their tasks.

The widespread popularity of Excel is often credited to its ubiquity and user-friendly learning curve. Yet, we want to think more deeply into this subject, as the driving force behind the creation of modelx was to incorporate the benefits of Excel into Python. What is it about Excel that instills such comfort in its users compared to Python?

Python Runs, Excel Persists

A Python program runs. Python executes a script from the start of the file through to the end. Before the program is executed, it’s simply a text file. While running, it exists for a short period, and once it finishes, it reverts back to being just a text file.

In contrast, Excel doesn’t “run” in the traditional sense. It doesn’t have a “Run” button, and it persists. It’s static and holds the results of your formulas at all times.

Which do you find more comfortable with: an entity that needs to be running to get a job done, or one that remains constant, always ready to present results?

Loop or recursion

How would you calculate the present value of cashflows in Python? Your code might look like:

pv = 0

for i in range(10):

pv += cashflow[i] / (1 + 0.5)**(i + 1)

Or if you prefer a more Pythonic approach, you might write:

pv = sum(cashflow[i] / (1 + 0.5)**(i + 1) for i in range(10))

Either way, the same logic is looped, and intermediate values,

such as pv at i=5 or cashflow[i] / (1 + 0.5)**(i + 1),

are not retained once the loop finishes.

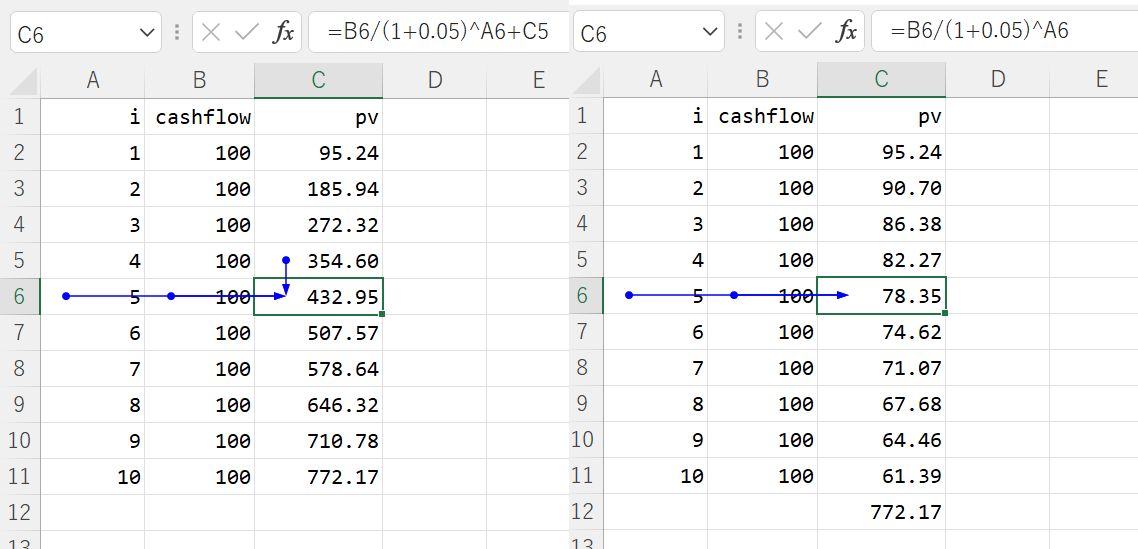

Now, consider the Excel approach:

As you see on the left, Excel uses recursion instead of loop to repeat the same formula,

so pv for all the i are available. On the right are a different way of taking the present value.

In this case, cashflow[i] / (1 + 0.5)**(i + 1) for all the i are retained.

Excel retains and displays the intermediate values used to arrive at the final result, allowing you to verify formula dependencies and ensure accuracy.

Coupling Formulas and Values

In Excel, a formula and its resulting value are tied together within the same cell. As long as Excel is set to automatic calculation mode, you can trust that the displayed value is up-to-date and will reflect any changes to the formula.

In Python, a piece of code and its result are separate entities. The result is stored in a variable (e.g., pv), which exists independently of the code that produced it. Even if the code changes, pv retains the old value until it’s explicitly updated, often by rerunning the entire script.

Singular Entry and Exit Points

A Python program has a single entry point and a single exit point, interpreting a script file from top to bottom. A segment of the program generally can’t run independently of its context.

Excel, on the other hand, has no explicit entry or exit points because it doesn’t “run” in the traditional sense. You don’t have to worry about the sequence of calculations or the evaluation order of formulas. Excel takes care of that, flagging any cyclic references.

Object-Oriented Nature

Excel is innately object-oriented. You might not even realize that you’re building a model in an object-oriented manner. There’s no need to define classes or methods, as objects (such as workbooks, worksheets, and ranges) are already provided for you to start defining formulas. This enables you to break down complex logic into manageable formula segments. In doing so, you naturally adhere to the best practice of splitting larger logic into components.

In Python, however, you might find yourself writing hundreds of lines of code in a single script file without defining any classes and methods. Starting with class and methods definitions from scratch in a plain text file can be challenging without the proper experience. Moreover, even if you are capable of doing so, your colleagues might not be.

The Design of modelx

modelx was developed to address these issues. Models in modelx function much like Excel workbooks. A modelx model doesn’t run; it persists. It retains all intermediate values, allowing you to trace formulas and their results. Formulas and their values are coupled. Models don’t have specific entry or exit points. Models are object-oriented, eliminating the need to write classes or methods. This is why the modelx catchphrase is “Use Python like a spreadsheet!”.